Highlights of the Central Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

- Apr 25, 2024

- 2 min read

One big openings week in Venice, surrounded by the theme "Foreigners everywhere." All that was there is almost impossible to capture in a single post, so I'll be sharing more Venice Spam over the next few days.

First and foremost, I extend huge congratulations to Adriano Pedrossa, the curator of this year's Biennale. His work in bringing queerness, tribal art, and "outsider" art to the forefront on such a global stage demands an applause. It is essential for inclusivity that we engage with the entire spectrum of the arts, and equally important to recognize and understand the position of 'the other'—and ourselves.

Walking through the Central Pavilion, one is struck by the façade that seems to narrate a story of the MAHKU collective (Movimento dos Artistas Huni Kuin)—painting a story of kapewe pukeni (the alligator bridge). This myth describes the passage between the Asian and American continents. In order to cross it, humans found alligators who offered to carry them across on their backs in exchange for food.

When you enter, you have three paths that lead to different narratives: portraits, abstracts, and other collective storytelling.

Gabrielle Goliath's work stood out—an installation with 15 screens that records the testimonies of black, brown, indigenous, femme, queer, non-binary, and trans individuals. You do not hear their voices, but you read their body language right before the speech. Breaths, swallows, and doubt—all these elements speak louder than words and reveal the harshness and trauma deeply embedded in their bodies.

I was also deeply moved by the subtle works of Evelyn Taocheng Wang. She is from Chengdu and lives in Rotterdam. Her work is about creating your own language while your roots are refracted with mildness and kindness to oneself.

The American, Liz Collins, fluidly moves between art and design. Her carpets radiate with queer energy and depict "the fantasy of a queer utopia that is just out of reach."

Sénèque Obin paints on masonite (hardboard made of steam-cooked and pressure-folded wood fibers). He offers a viewpoint that is so important to understanding the arts in the Americas in the mid-twentieth century. His work challenges the labels "self-taught," "naive," and "primitive," which are often applied to artists of color. You find paintings of Haitian culture and tradition—a beautiful depiction to be celebrated.

A stunning abstract by Palestinian artist Samia Halaby explores perspectives, round edges, curves, and cross-structures.

Miguel Ángel Rojas makes you watch through a peephole at illegal sexual encounters in cinemas in Colombia between men during the 1970s. It remains secretive and respectable. It is blurry and anonymous, yet full of respect.

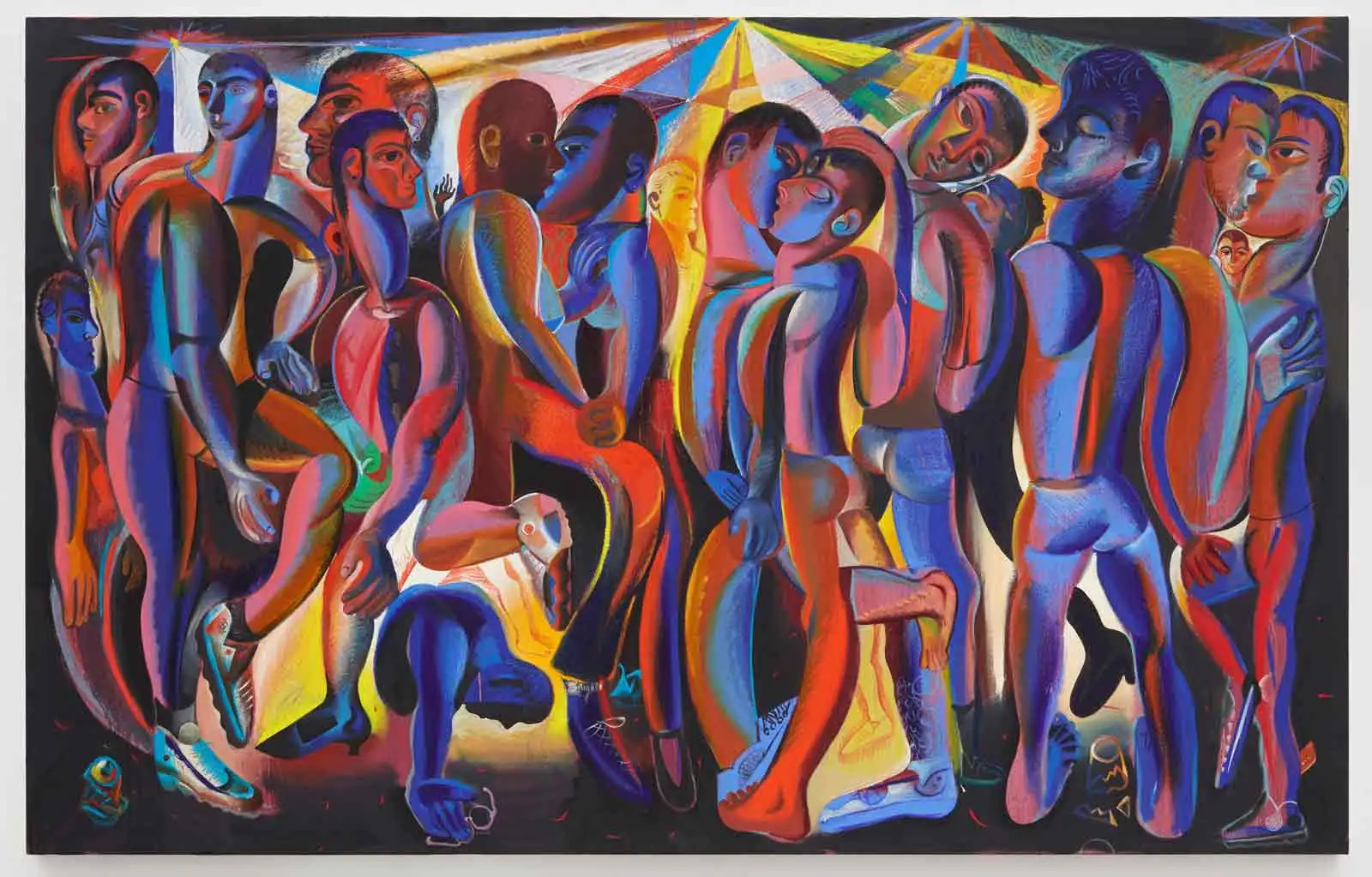

Lastly, the bodies in Louis Fratino’s homoerotic visuals show the body heat in the queer climate and serve as a political response to inequality.

This strong statement about considering the narratives of others is deeply touching. Inside, the works may feel slightly familiar, yet intriguingly, more than half of these artists have never been shown before. Adriano Pedrossa has highlighted the importance of uncanniness—the unsettling yet oddly familiar—that challenges our preconceptions. This feeling was palpable and rightly so. Why do these unfamiliar works seem known to us? Who are these people behind them, and why haven't we known them before? While some pieces might provoke discomfort, they primarily stimulate discussions towards a more inclusive and broad-minded art world.

Comments